Lecture 11: First-class Functions

1 First-class Functions

In Lecture 7: Defining functions, we introduced the ability for our programs to define functions that we could then call in other expressions in our program. Our programs were a sequence of function definitions, followed by one main expression. This notion of a program was far more flexible than we had before, and lets us define many computations we simply could not previously do. But it is distinctly unsatisfying: functions are second-class entities in our language, and can’t be used the same way as other values in our programs.

We know from other courses, and indeed even from writing compilers in ML, that

higher-order functions —

def applyToFive(it):

it(5)

def incr(x):

x + 1

applyToFive(incr)Do Now!

What errors currently get reported for this program?

Because it is a parameter to the first function, our compiler will

complain that it is not defined as a function, when used as such on line

2. Additionally, because incr is defined as a function, our compiler will

complain that it can’t be used as a parameter on the last line. We’d like to

be able to support this program, though, and others more sophisticated. Doing

so will bring in a number of challenges, whose solutions are detailed and all

affect each other. Let’s build up to those programs, incrementally.

2 Reminder: How are functions currently compiled?

Let’s simplify away the higher-order parts of the program above, and look just at a basic function definition. The following program:

def incr(x):

x + 1

incr(5)is compiled to:

incr:

push EBP ;; stack frame management

mov EBP, ESP

mov EAX, [EBP + 8] ;; get param

add EAX, 2 ;; add (encoded) 1 to it

mov ESP, EBP ;; undo stack frame

pop EBP

ret ;; exit

our_code_starts_here

push EBP ;; stack frame management

mov EBP, ESP

push DWORD 10 ;; push (encoded) 5

call incr ;; call function

add ESP, 4 ;; remove arguments

mov ESP, EBP ;; undo stack frame

pop EBP

ret ;; exitThis compilation is a pretty straightforward translation of the code we have. What can we do to start supporting higher-order functions?

3 The value of a function —

3.1 Passing in functions

Going back to the original motivating example, the first problem we encounter is seen in the first and last lines of code.

def applyToFive(it):

it(5)

def incr(x):

x + 1

applyToFive(incr)Functions receive values as their parameters, and function calls push values

onto the stack. So in order to “pass a function in” to another function, we

need to answer the question, what is the value of a function? In the

assembly above, what could possibly be a candidate for the value of the

incr function?

A function, as a standalone entity, seems to just be the code that comprises its compiled body. We can’t conveniently talk about the entire chunk of code, though, but we don’t actually need to. We really only need to know the “entrance” to the function: if we can jump there, then the rest of the function will execute in order, automatically. So one prime candidate for “the value of a function” is the address of its first instruction. Annoyingly, we don’t know that address explicitly, but fortunately, the assembler helps us here: we can just use the initial label of the function, whose name we certainly do know.

In other words, we can compile the main expression of our program as:

our_code_starts_here

push EBP ;; stack frame management

mov EBP, ESP

push incr ;; push the start label of incr

call applyToFive ;; call function

add ESP, 4 ;; remove arguments

mov ESP, EBP ;; undo stack frame

pop EBP

ret ;; exitThis might seem quite bizarre: how can we push a label onto the stack?

Doesn’t push require that we push a value —calling a label in the first place: the assembler replaces

those named labels with the actual addresses within the program, and so at

runtime, they’re simply normal DWORD values representing memory

addresses.

3.2 Using function arguments

Do Now!

The compiled code for

applyToFivelooks like this:our_code_starts_here push EBP ;; stack frame management mov EBP, ESP mov EAX, [EBP + 8] ;; get the param push ???? ;; push the argument to `it` call ???? ;; call `it` add ESP, 4 ;; remove arguments mov ESP, EBP ;; undo stack frame pop EBP ret ;; exitFill in the questions to complete the compilation of

applyToFive.

The parameter for it is simply 5, so we push 10 onto the stack,

just as before. The function to be called, however, isn’t identified by its

label: we already have its address, since it was passed in as the argument to

applyToFive. Accordingly, we call EAX in order to find and call our

function. Again, this generalizes the syntax of call instructions

slightly just as push was generalized: we can call an address given by a

register, instead of just a constant.

3.3 Victory!

We can now pass functions to functions! Everything works exactly as intended.

Do Now!

Tweak the example program slightly, and cause it to break. What haven’t we covered yet?

4 The measure of a function —

Just because we use a parameter as a function doesn’t mean we actually

passed a function in as an argument. If we change our program to

applyToFive(true), our program will attempt to apply true as a

function, meaning it will try to call 0xFFFFFFFF, which isn’t likely to

be a valid address of a function.

As a second, related problem: suppose we get bored of merely incrementing values by one, and generalize our program slightly:

def applyToFive(it):

it(5)

def add(x, y):

x + y

applyToFive(incr)Do Now!

What happens now?

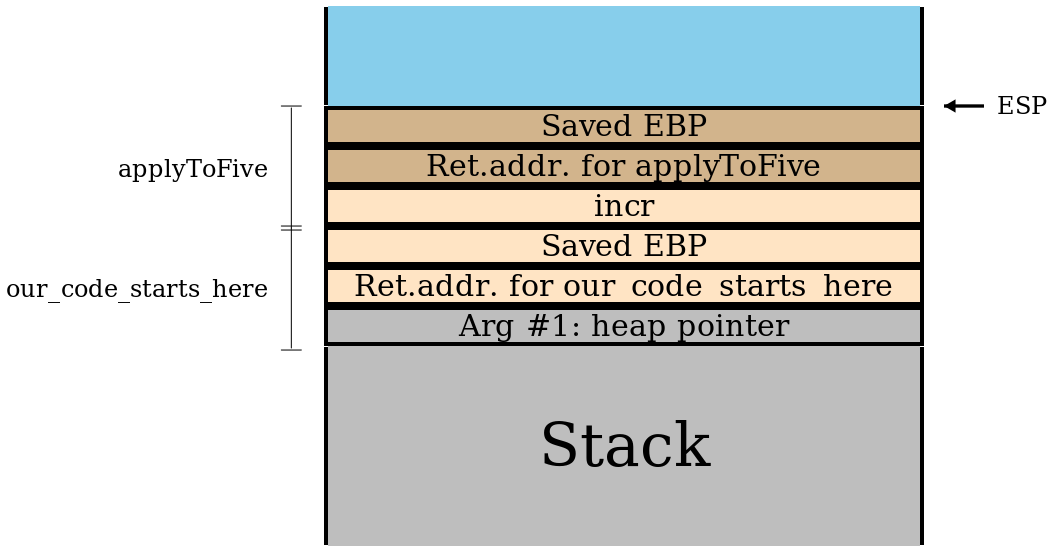

Let’s examine the stack very carefully. When our program starts, it pushes

incr onto the stack, then calls applyToFive. (The colors

indicate which functions control the data on the stack, while the

brackets along the side indicate which function uses the data on the

stack; explaining why they don’t quite align at function-argument positions.)

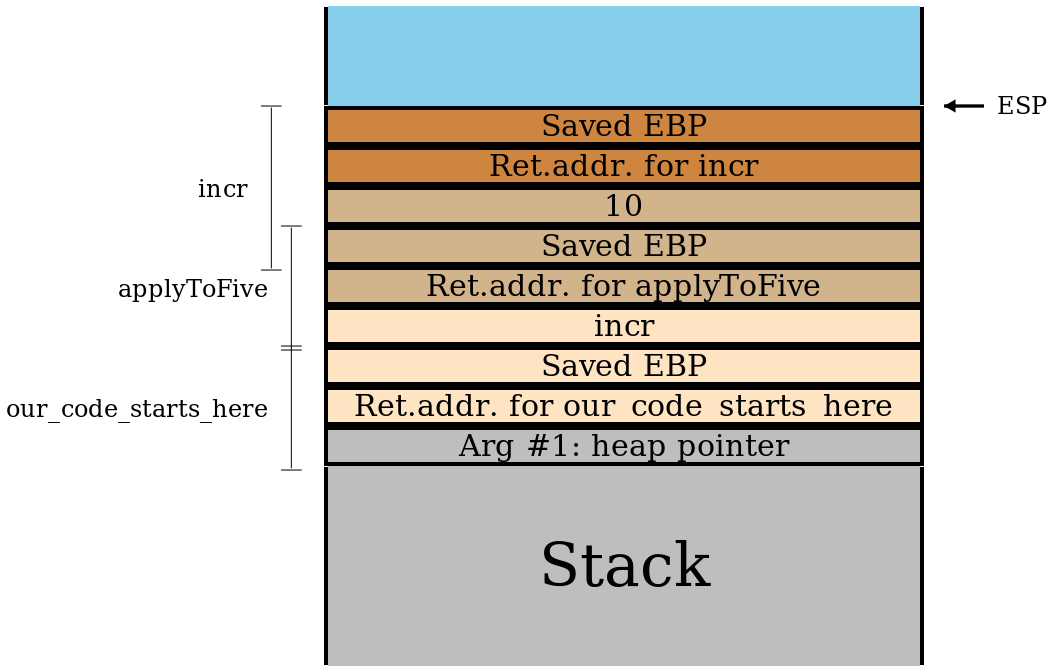

That function in turn pushes 10 onto the stack, and calls it

(i.e. the address currently stored in EAX):

But look at the bracketing for incr! It needs two arguments, but

receives only one. So it adds 5 (encoded as 10) to the saved

EBP, since as far as it knows that stack location is where its second

parameter should be.

We had eliminated both of these problems before via well-formedness checking: our function-definition environment knew about every function and its arity, and we could check every function application to ensure that a well-known function was called, with the correct number of arguments were passed. But now that we can pass functions around dynamically, we can’t know statically whether the arities are correct, and can’t even know whether we have a function at all!

We don’t know anything about precisely where a function’s code begins, so there’s no specific property we could check about the value passed in to determine if it actually is a function. But in any case, that value is insufficient to encode both the function and its arity. Fortunately, we now have a technique for storing multiple pieces of data as a single value: tuples. So our second candidate for “the value of a function” is a tuple containing the function’s arity and start address. This isn’t quite right either, since we wouldn’t then be able to distinguish actual tuples from “tuples-that-are-functions”.

So we choose a new tag value, say 0x5, distinct from the ones used so

far, to mark these function values. Even better: we now have free rein to

separate and optimize the representation for functions, rather than hew

completely to the tuple layout. As one immediate consequence: we don’t need to

store the tuple length —

Do Now!

Revise the compiled code of

applyToFiveto assume it gets one of the new tuple-like values.

The pseudocode for calling a higher-order function like this is roughly:

mov EAX, <the function tuple> ;; load the intended function

<check-tag EAX, 0x5> ;; ensure it has the right tag

sub EAX, 5 ;; untag the value

<check-arity [EAX], num-args> ;; the word at [EAX] stores the arity

<push all the args> ;; set up the stack

call [EAX+4] ;; the second word stores the function address

add ESP, <4 * num-args> ;; finish the callNow we just need to create these tuples.

Exercise

Revise the compiled code above to allocate and tag a function value using this new scheme, instead of a bare function pointer.

Even if we want to represent functions as these tuple-like values, where should we store such tuples? We now have a disparity between “normal” function calls, where we know the name comes from a top-level declaration in the source program, and “higher-order” function calls, where the function to be called comes in as a parameter.

4.1 Aside: A general tag-checking instruction sequence

Now that we have several tags to check, it’s worth rethinking how we check them, to see whether there’s some commonality among them. Our tags fall into two distinct groupings: numbers, and everything else. Number-tags are distinct because they’re only one bit long; the others are all three bits long. Let’s try to handle each group individually. We have two related tasks: checking whether a value has a given tag (and branching accordingly), and creating a boolean value asserting whether a value has a given tag.

4.1.1 Testing and branching

Checking whether a value is a number is straightforward. We need to look at

the one’s bit only: if it is zero, we have a number; if it isn’t, we don’t. We

can implement this with just two instructions, assuming the value we are

testing is already in EAX: test EAX, 0x1 / jnz not_a_num.

Checking whether a value is a boolean or a tuple is also straightforward. We

need to look at the lowest three bits, and see if they are all set. We can do

this with a three instruction sequence, assuming the value we are testing is

already in EAX: and EAX, 0x7 / cmp EAX, <tag>

/ jne not_a_<tag-type>. The 0x7 masks off just the lowest three bits,

while the comparison checks whether those remaining bits are equal to the

desired tag: 0x7 for booleans, 0x1 for tuples, etc.

4.1.2 Creating boolean values

Creating a boolean based on these results is slightly less simple. We

could just use the results above, and then on either arm of the branch,

move the appropriate boolean into EAX. But branches can be expensive,

especially when they aren’t predictable by the processor,1Look up “branch

prediction misses” for more information. so an alternate solution without

branches is preferable. In practice, any sequence of fewer than ten unbranched

instructions will be faster than the branch solution.2There also exist

conditional

moves, which are a contraction of a branch and a move instruction. These can

be expensive, too, so

avoiding them may also be warranted. But there’s (at least!) one clever

solution.

Given that the goal is to create a boolean value, we just need to get a 1 or a

0 into the MSB of our answer; after that, we can just set all the other bits to

one (via or EAX, 0x7fffffff) to get a proper boolean result. So the

question boils down to, how can we get a one into the MSB if and only if the

value has the tag we want? For numbers, the result is easy. We already have a

zero in the one’s bit when the value is a number, and a one bit otherwise. So,

if we shift the value 31 bits left and invert it, we get the bit we need. This

leads to a three-instruction sequence, assuming the value to be tested

currently is in EAX: shl EAX, 31 /

xor EAX, 0xffffffff / or EAX, 0x7fffffff.

For our other tags, we need to test multiple bits at once. One obvious place

to start is by masking off all but the tag bits, as we did above. Now we have

exactly three bits for our tag, and zeros elsewhere. How does that help?

Observe that when we tried to check whether a value was a number, we found a

specific bit —

Let’s load the value to be tested into ECX, and then mask off the tag

bits via and ECX, 0x7. Then, let’s simply load a single bit into

EAX: mov EAX, 1. If we treat the tag (in the low-order byte of

ECX) as a number, we can associate a bit with each tag: we’d like

to move that 1-bit in EAX into the eighth bit if the tag is 0x7,

into the second bit if the tag is 0x1, etc. In other words, we’d like to

compute 2tag, and we can do so using shl: shl EAX, CL.

(The second argument specifies the low-order byte of the ECX register.)

Now that we’ve moved the single 1-bit to a distinct place, depending on the tag

bits that we actually have, we can shift the EAX value by some more

places depending on the tag bits we want to have. As a result, the

1-bit will wind up in the MSB if and only if the tag bits we have equal the tag

bits we want:

mov ECX, <value to test> ;; load up the value

and ECX, 0x7 ;; mask off the non-tag bits

mov EAX, 1 ;; load a single 1-bit

shl EAX, CL ;; move it left by #bits = tag we have

shl EAX, <31 - tag> ;; move it again by the #bits = tag we want

or EAX, 0x7fffffff ;; set the remaining bits5 A function by any other name —

The crux of the problem now is that some of our functions are “real”

functions that were defined by def and whose addresses and arities are

known, whereas some function are “passed-in” functions that are represented

as tuples. Because of this distinction, we don’t have any good, uniform way to

handle compiling function calls. In particular, we don’t have an obvious place

in our compilation to create those tuples.

What if we revise our language, to make functions be just another expression form, rather than a special top-level form? We’ve seen these in other languages: we call them lambda expressions, and they appear in pretty much all major languages:

Language |

| Lambda syntax |

Haskell |

|

|

Ocaml |

|

|

Javascript |

|

|

C++ |

|

|

We can rewrite our initial example as

let applyToFive = (lambda it: it(5)) in

let incr = (lambda x: x + 1) in

applyToFive(incr)Now, all our functions are defined in the same manner as any other let-binding: they’re just another expression, and we can simply produce the function values right then, storing them in let-bound variables as normal. Let’s try compiling a simplified version of this code:

let incr = (lambda x: x + 1) in

incr(5)Our compiled output will look something like this:

our_code_starts_here:

push EBP

mov EBP, ESP

incr:

push EBP

mov ESP, EBP

mov EAX, [EBP+8]

add EAX, 1

mov ESP, EBP

pop EBP

ret

mov EAX, ESI ;; allocate a function tuple

or EAX, 0x5 ;; tag it as a function tuple

mov [ESI+0], 1 ;; set the arity of the function

mov [ESI+4], incr

add ESI, 8

mov [EBP+8], EAX ;; let incr = ...

mov EAX, [EBP+8]

<check that EAX is tagged 0x5>

sub EAX, 5

<check that EAX expects 1 argument>

push 10

call [EAX+4]

add ESP, 4

move ESP, EBP

pop EBP

retDo Now!

What’s wrong with this code?

Our program will start executing at our_code_starts_here, and flows

straight into the code for incr, even though it hasn’t been called!

We seem to have left out a crucial part of the semantics of functions: while a

function is defined by its code, that code should not run until it’s

called: lambda-expressions are inert values.

Do Now!

What simple code-generation tweak can we use to fix this?

On the one hand, the code shouldn’t be run. On the other, we have to emit the code somewhere. There are two possible solutions here:

We can transform our program even further, to somehow lift all the lambdas out from the innards of other functions so that we regain the “every function lives at the top level” structure of our old code. This approach, called lambda-lifting, works well, but is overkill for our purposes for now.

Another is simply to label the end of the function, and just add a

jmp end_labelinstruction before the initial label. We then bypass the code of the function when we’re “defining” it, but when wecallit, we skip thejmpand start right at the first instruction of the code.

Exercise

Compile the original example to assembly by hand.

5.1 Making it work: ANF

Exercise

Define the ANF transformations for lambda expressions and function-applications. Should lambdas be considered immediate, compound, or just ANF expressions? What about the various subexpressions of function-applications?

6 “Objects in mirror may be closer than they appear” —

Our running example annoyingly hard-codes the increment operation. Let’s generalize:

let add = (lambda x: (lambda y: x + y)) in

let applyToFive = (lambda it: it(5)) in

let incr = add(1) in

let add5 = add(5) in

(applyToFive(incr), applyToFive(add5))Exercise

What does this program produce? What goes wrong here? Draw the stack demonstrating the problem.

Our representation of functions cannot distinguish incr from add5:

they have the same arity, and point to the same function. But they’re clearly

not the same function! This is a problem of scope. How can we

distinguish these two functions?

6.1 Bound and free variables

What does incr actually evaluate to? A function-tuple (1, <code>)

where the code is the compiled form of lambda y: x + y. How exactly does

that expression get compiled? When we compile the expression x + y, we

have an environment where x is mapped to “the first function parameter”,

and so is y. In other words, this expression gets compiled to the

same thing as y + y —x and

y really are the first function parameters of their respective functions,

but within the inner lambda, those descriptions come into conflict.

Define a variable x as bound within an expression e if

xappears on the left side of a let-binding, oreis a lambda expression andxappears as one of its parameters

Define a variable to be free if it is not bound. For instance, in

let x = lambda m: let t = m in x + t

in x + yyis certainly free within the entire expression: there are no bindings for it at all.xis free within the lambda: its only binding appears outside that lambdaThe uses of

mandtare bound, by the lambda’s parameter and by the inner let-binding, respectively.

Now we can see the problem with our add5 and incr example: x is

free within the lambdas for those two functions, but our compiled code does not

take that into account. We can generalize this problem easily enough: our

compilation of all free variables is broken.

6.2 Computing the set of free variables

We need to know exactly which variables are free within an expression, if we want to compile them properly. This can be subtle to get right: because of shadowing, not every identifier that’s spelled the same way is in fact the same name. (We saw this a few lectures ago when we discussed alpha-equivalence and the safe renaming of variables.) It’s easy to define code that appears right, but it’s tricky to convince ourselves that the code in fact is correct.

Do Now!

Define a function

freeVars : 'a aexpr -> string listthat computes the set of free variables of a given expression.

Now what?

6.3 Using free variables properly: achieving closure

We know from using lambdas in other languages what behavior we expect from them: their free variables ought to take on the values they had at the moment the lambda was evaluated, rather than the moment the lambda’s code was called.3Think carefully about what your intuition is here, when a free variable is mutable... We say that we want lambdas to close over their free variables, and we describe the value of a function as a closure (rather than the awkward “function-tuple” terminology we’ve had so far). To accomplish this, we clearly need to store the values of the free variables in a reliable location, so that the compiled function body can find them when needed...and so that distinct closures with the same code but different closed-over values can behave distinctly! The natural place to store these values is in our tuple, just after the function-pointer. This leads to our latest (and final?) representation choice for compiling first-class functions.

Let’s work through a short example:

let five = 5 in

let applyToFive = (lambda it: it(five)) in

let incr = (lambda x: x + 1) in

applyToFive(incr)First, let’s focus on the compilation of the let-binding of applyToFive:

our closure should be a triple (arity = 1, code = applyToFive, five = 5),

where I’ve labelled the components for clarity.

...

mov EAX, 5

mov [EBP+8], EAX ;; let five = 5 in ...

jmp applyToFive_end

applyToFive:

...

applyToFive_end:

mov [ESI+0], 1 ;; set the arity of the function

mov [ESI+4], applyToFive ;; set the code pointer

mov EAX, [EBP+8] ;; load five

mov [ESI+8], EAX ;; store it in the closure

mov EAX, ESI ;; start allocating a closure

add EAX, 0x5 ;; tag it as a closure

add ESI, 16 ;; bump the heap pointer, maintaining 8-byte alignment

mov [EBP+8], EAX ;; let applyToFive = ...

...Do Now!

This example shows only a single closed-over variable. What ambiguity have we not addressed yet, for closing over multiple variables?

7 Implementing the new compilation

7.1 Scope-checking

Exercise

What should the new forms of well-formedness and scope checking actually do? What needs to change?

7.2 Compiling function bodies

Now we just need to update the compilation of the function body itself, to look for closed-over variables in the correct places. Let’s agree to stash the variables in alphabetical order, so that we have a canonical representation for each closure. We can codify this understanding by updating the environment we use when we compile a function body. We have two options here:

We can repeatedly access each free variable from the appropriate slot of the closure

We can unpack the closure as part of the function preamble, copying the values onto the stack as if they were let-bound variables, and offsetting our compilation of any local let-bound variables by enough slots to make room for these copies.

Exercise

What are some of the design tradeoffs of these two approaches?

We’ll implement the second approach.

let rec compile_cexpr (e : tag cexpr) si env =

match e with

| CLambda(args, body) ->

let free = List.sort (freeVars e) in

let moveClosureVarToStack idx =

IMov(RegOffset(~4 * i, EBP), (* move the i^th variable to the i^th slot *)

RegOffset(8 + 4*i, ???)) (* from the (i+2)^nd slot in the closure *)

in let newEnv = (List.map_i (fun fv i -> moveClosureVarToStack i) free) @ env in

let compileBody = compile_aexpr body (List.length free) newEnv in

...Do Now!

What can we use to fill the question-marks?

The compiled function body needs access, at runtime, to the closure itself in order to retrieve values from out of it!

Do Now!

Would this problem be any different if we’d implemented the first approach above?

7.3 Compiling function calls

We need to change how we compile function applications, too, in order to make our compilation of closures work. Let’s agree to change our calling signature, such that the first argument to every function call is the closure itself. In other words, the compilation of function calls will now look like:

Retrieve the function value, and check that it’s tagged as a closure.

Check that the arity matches the number of arguments being applied.

Push all the arguments..

Push the closure itself.

Call the code-label in the closure.

Pop the arguments and the closure.

7.4 Revisiting compiling function bodies

Our function bodies will now be compiled as something like

Compute the free-variables of the function, and sort them alphabetically.

Update the environment:

All the arguments are now offset by one slot from our earlier compilation

All the free variables are mapped to the first few local-variable slots

The body must be compiled with a starting stack-index that accommodates those already-initialized local variable slots used for the free-variables

Compile the body in the new environment

Produce compiled code that, after the stack management and before the body, reads the saved free-variables out of the closure (which is passed in as the first function parameter), and stores them in the reserved local variable slots.

The closure itself is a heap-allocated tuple (arity, code-pointer, free-var1, ... free-varN).

7.5 Revisiting our runtime

All our runtime-provided functions, like print or equal, now no longer

work with our new calling signature: we provide one too many arguments. Worse,

before we could identify all functions by their starting label, and

runtime-provided functions had starting labels too. Now, we need closures, but

our runtime-provided functions don’t have such things.

Exercise

Repair the runtime-provided functions somehow. There are at least two possible designs here, probably more... What are the tradeoffs among them?

7.6 Victory!

We can now pass functions with free-variables to functions! Everything works exactly as intended.

Do Now!

Break things, again.

8 Recursion

If we try even a simple recursive function, that worked with our previous top-level function definitions, we run into a problem. Because we now only have let-bindings and anonymous lambdas, we have no way to refer to the function itself from within the function. We’ll get a scope error during well-formedness checking; such a program wouldn’t even make it to compilation.

let fac = (lambda n:

if n < 1: 1

else: n * fac(n - 1)) # ERROR: fac is not in scope

in fac(5)This is precisely why ML has a let rec construct: we need to inform our

compiler that the name being bound should be considered as bound within the

binding itself.4That’s a twisty description, but then again, we

are dealing with recursion... But not just every expression can be

considered recursively bound:

let rec x = x + x in "this is nonsense"Pretty much, only functions can be let-rec-bound: they are the only form of

value we have that does not immediately trigger computation that

potentially uses the name-being-bound. They are deferred computation, awaiting

being called.5Lazy languages, like Haskell, allow some other recursive

definitions that are not explicitly functions, such as

let ones = 1 : ones. Essentially, all values in lazy languages

are semantically equivalent to zero-argument functions, that are only called at

most once, when truly needed (and whose values are cached, so they’re never

recomputed); these implicit thunks are how these recursive definitions

can be considered well-formed. The particular example above, though, of

let rec x = x + x, would not work in Haskell either: addition requires its

arguments, so laziness or not, x is still not yet defined by the time it

is needed. We have a choice: we can introduce a new syntactic form for these

let-rec-bound variables, or we can introduce a new well-formedness check.

Syntactically, we might write

def fac(n): ... in

fac(5)where def ... in is like let ... in, but for recursive functions.

Exercise

What are some advantages and disadvantages of these two approaches?

Exercise

Extend the compilation above to work for recursive functions.

8.1 Victory!

We can now pass functions with free-variables to functions and to themselves! Everything works exactly as intended.

Do Now!

Break things, again.

Exercise

Fix things, again.

1Look up “branch prediction misses” for more information.

2There also exist conditional moves, which are a contraction of a branch and a move instruction. These can be expensive, too, so avoiding them may also be warranted.

3Think carefully about what your intuition is here, when a free variable is mutable...

4That’s a twisty description, but then again, we are dealing with recursion...

5Lazy languages, like Haskell, allow some other recursive

definitions that are not explicitly functions, such as

let ones = 1 : ones. Essentially, all values in lazy languages

are semantically equivalent to zero-argument functions, that are only called at

most once, when truly needed (and whose values are cached, so they’re never

recomputed); these implicit thunks are how these recursive definitions

can be considered well-formed. The particular example above, though, of

let rec x = x + x, would not work in Haskell either: addition requires its

arguments, so laziness or not, x is still not yet defined by the time it

is needed.